Adam Rosman spent much of March in the Hluhluwe Imfolozi Park, in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN). Unlike a conventional tourist, Rosman wasn't searching for the big five from the back of a game-viewing vehicle - he was scouting for poachers using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones.

The aeronautical engineer works for Shaya Technologies, which was tasked by the park to assist in its efforts to curb rhino poaching. The IT security company, owned by Ian Melamed, opted to do so from above.

"The point of the whole UAV move was to trial the use of drones as an anti-rhino poaching tool," says Rosman, adding that the focus on KZN wildlife is fitting, as the area has the largest collection of rhino in the country. Shaya Technologies' anti-poaching drones make use of small airplanes with some form of monitoring system on board. He describes them as "flying CCTV cameras".

"We face an unprecedented poaching crisis. Killings are way up. We need solutions that are as sophisticated as the threats we face," says Carter Roberts, president and CEO of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). Roberts notes this increased poaching threat means conservationists have to push the envelope in the fight against wildlife crime.

Eye in the sky

The fact that the R618, a public road, runs through the middle of the park, with no fences limiting its use, is one of the main concerns at Hluhluwe. Rangers have often found that poachers would drive along the road, shoot a rhino, hack off its horn, and then hop in their cars and leave, says Rosman. "We monitored this road. What we picked up with the drones were a few cases of cars suspiciously pulled over on the side of the road. We would just fly over with the drones to make it known they were being monitored, and in most cases, the people would quickly drive off," says Rosman.

"Although it is tempting to fit the drones with weapons that could blow up poachers, our main focus is surveillance and reaction," Rosman jokes. He adds that this kind of monitoring proves especially valuable in large areas, where there just isn't enough manpower to keep an eye on everything.

Myths about rhino horn

The market for rhino horn is largely driven by demand from the East. Many eastern cultures believe the horn:

* Is a coming of age status symbol (Yemen);

* A cure for cancer;

* An aphrodisiac;

* A remedy to combat rheumatism, gout, fever, and other illnesses;

* When carved into a vessel, can purify water; and

* Is capable of detecting poisons.

Two types of drones were used during the pilot project at Hluhluwe. The first have a 3.5m wingspan, are powered by a petrol motor, and can stay in the air for five to six hours. These aircraft stream real-time footage to the team on the ground, says Rosman. The drones in the second fleet are smaller, electric hex rotor copters. These are typically the reaction drones, used for close monitoring. "If a game ranger hears a gunshot, they have about 40 minutes to react before the poachers get away. The beauty of the smaller hex copters is that they can be launched in five minutes. They don't have the same endurance as the larger drones, but they are intended for quick response."

According to Rosman, the drones do not run autonomously - a pilot and operator are assigned to each device and a ground control station situated near the runway keeps tabs on what the aircraft are doing. The team on the ground communicates with the drones via a video and telemetry connection, which allows the pilot to monitor onboard sensors, gauges and GPS systems in the same way as a conventional pilot would monitor these things while flying a normal aircraft. The pilot will intervene if the device is doing something unusual, or if something goes wrong, notes Rosman.

"The operator runs the autopilot systems - setting up the flight path and programming the drone," he says, adding there is also a maintenance team. According to Rosman, pilots are still involved in the takeoff and landing, but once this has been fine-tuned by the Shaya team, the drones will be able to take off and land unassisted. "These devices can be controlled using a generic gaming joystick. You can even use an Xbox controller to fly our drones."

The system is not without its issues, says Rosman. During the trial in KZN, one of the drones clipped the top of a tree and crashed. But the team was able to retrieve the device using onboard GPS data. To mitigate any risks that a crashed UAV could start a fire, the devices have been fitted with onboard fire suppression systems.

While the project has started off with small trials, the ultimate plan is to roll it out extensively and to tailor the devices to cater to the unique needs of each park. According to Rosman, during the month-long demo in KZN, not a single rhino was poached.

Poaching in numbers

The number of rhino killed in SA has risen drastically over the years. Fortunately, arrests have also increased.

* 2010 - 333 animals poached; 165 arrests

* 2011 - 448 animals poached; 232 arrests

* 2012 - 668 animals poached; 267 arrests

* 2013 - 273 animals poached as of end April; 83 arrests so far

The aim of the demo in Hluhluwe was to showcase the capabilities of the technology and to tweak Shaya's set-up of the solution. "I think this technology can make a huge difference. It will help parks, like Hluhluwe, to use their resources more effectively. These drones mean that park rangers won't have to waste manpower monitoring roads and fences, allowing park officials to use the rangers more efficiently," he says.

The team has several demos set up in the coming months, and there has been interest from other parks and companies in other industries, says Rosman. "We offer a managed solution. We don't just sell a company a drone; we also provide the pilots and operators to get the surveillance running smoothly. We tailor-make the offering to each company as it needs it." According to Rosman, the current focus is on demonstrations, and once the contracts come in, Shaya will finalise pricing structures and offerings to tackle each problem.

Fighting fire with tech

Seeing the need to change its wildlife preservation strategies, the WWF has also embarked on a new approach to curb illegal wildlife trade - creating an umbrella of technologies to protect endangered animals.

"Poachers are stepping up their game and becoming more determined and better resourced," says Crawford Allan, WWF's illegal wildlife trade expert. "Years of conservation investment is being lost rapidly, as governments struggle to cope with the onslaught."

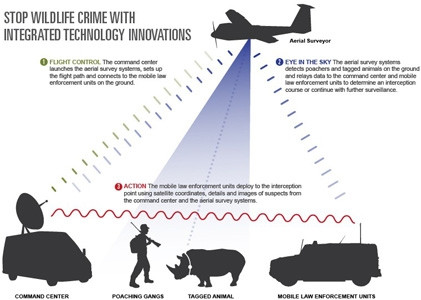

According to Allan, the wildlife conservation organisation is investing the $5 million Global Impact Award grant it received from Google in helping governments implement specialised intelligent technology programmes. The programmes will feature aerial surveillance systems and affordable wildlife tagging technology, coupled with cost-effective ranger patrolling and analytical software, all of which aims to improve the detection and prevention of illegal poaching.

The Google grant will fund the purchase of various anti-poaching technologies. Using cellphone (GSM) technology, the WWF is set to implement affordable animal tracking systems, in addition to deploying a fleet of drones to monitor the situation from above. The WWF will also equip rangers with the Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool, a hi-tech application built to improve the effectiveness of conservation management. The partnership with Google marks the first time the WWF has undertaken such an approach, notes Allan.

On the ground, in the air

Four sites in Asia and Africa have already been selected as focus areas for the deployment of the anti-poaching technologies, says Allan.

One such effort focuses on elephants, which are being slaughtered en masse for their ivory tusks. The WWF has deployed UAVs to combat poaching of the pachyderms in various locations where rangers are unable to keep up with the illegal wildlife trade. "It will be a great advantage to protect both wildlife and the rangers," Allan says. "We will know where the animals are, the [drone] relays the location to ground control, and you can mobilise rangers on the ground to get in between the animals and form a shield. We see this as an umbrella of technology."

According to Alan, the WWF has already demoed similar aerial technology in Nepal's national parks, which are home to endangered rhinos, tigers and elephants. Anti-poaching efforts in this region received a boost when the WWF trained 19 park rangers and Nepal Army members on how to use UAVs and conduct field tests.

"As the global poaching crisis escalates, WWF is excited by the potential of technologies like UAVs to aid rangers on the frontline and better protect Nepal's natural heritage," said Shubash Lohani, deputy director of WWF's Eastern Himalayas Programme. "We hope this field test will not only improve protection of Nepal's national parks, but also gain new champions in other vulnerable places around the world."

It is not only the WWF using UAVs to combat wildlife criminals. The Ol Pejeta conservancy, in Kenya, will unleash a drone to provide additional monitoring of illegal activity in the area in the coming weeks. Robert Breare, who deals with strategy and innovation at Ol Pejeta, notes poaching in the area is out of control, forcing the team at Ol Pejeta to do something about it.

"Poaching has reached pretty epic levels, most notably in rhinos and elephants," he says. "One of the problems when you have thousands of acres of wilderness is that it's near impossible to be at all places at once, especially when you only have a handful of rangers patrolling. What this does is put an 'eye in the sky' to monitor things we just can't see from the ground."

A separate initiative, by a group called Conservation Drones, is already utilising drone aircraft at as many as 20 sites around the world. One of its projects involves using drones to count orangutan nests in the dense jungles of Sumatra, Indonesia. Making use of high-definition cameras and GPS-mounted navigation software, drones are able to cover large territories in less time than ground-based crews, says Serge Wich, professor of primate biology at Liverpool John Moores University. "To do several line transects to count orangutan nests would take us three days. A drone can do it in 20 minutes."

"We don't want people to see the drone as a silver bullet solution and expect there to be a sudden halt in poaching," says Breare. "There's an epidemic right now, but this is just one part of an overall armoury we are using to tackle it."

High profit, combined with minimal risk, has allowed wildlife crime to become an illegal activity worth as much as $10 billion annually.

And the world is paying the price.

"I don't know if projects like ours will ever be able to completely stop poaching," concludes Rosman. "But if we can make it a little harder for these criminals to poach, then we have achieved something."

Share